Doxological Pedagogy (Part Three)

A Still More Excellent Way

It would be an interesting (even if ultimately infuriating) exercise to imagine Dante, coming out of the wood, meeting either Socrates or Jean-Jaques instead of Vergil. What would his journey have looked like under the tutelage of either of these philosophers? Where would Dante have been taken, if the governing assumption was that Dante was basically good, and simply had misaligned knowledge, or misaligned sentiments, and not (as was actually the case) misaligned loves and a broken will?

We will have occasion to return to these deficient worldviews at different points later in our discussion, focusing on how they have shaped the ultimately ineffective philosophy of education held by secularism, as well as the resultant pedagogy employed in our schools today. Let it suffice at this point to draw the contrast between the humanistic optimism of both Plato and Rousseau, and the biblical answer to the question, “What is man?” According to the Word, man is the created image-bearer of the Triune God, created male and female, created perfect and innocent. At the same time, following the events of the Garden of Eden, man is now fallen, and fundamentally at odds with God and thus with our created purpose. The biblical answer to the question, “What is man for?” is that man was created to glorify God, enjoy Him forever, and to do so through being fruitful and multiplying, taking dominion of the earth (Genesis 1:28), and bringing all things back to God in worship (Matthew 28:18-20). The Fall skews and corrupts our ability to live consistent with our created telos. Now, our fundamental posture, born in sin, is the desire to do all things with reference to self — to love and worship self, instead of Almighty God. This is the basis for every man-centered philosophy of education: man’s naive and groundless optimism to be able to accomplish our created purpose without submitting to our Creator. All man-centered expressions of education, therefore, are necessarily selfish, and ultimately vain, given man’s actual created purpose.

Memory, Understanding, and Love

Augustine, in his great work on the Trinity, captures the two alternate paths with great clarity, identifying both what we are as image-bearing creatures, and what we are for. He writes:

[We bear the image of God not] because the mind remembers itself, and understands and loves itself; but because it can also remember, understand, and love Him by whom it was made. And in so doing it is itself made wise. But if it does not do so, even when it remembers, understands, and loves itself, then it is foolish. Let it then remember its God, after whose image it is made, and let it understand and love Him. Or to say the same thing more briefly, let it worship God, who is not made… wherefore it is written, “Behold, the worship of God, that is wisdom.” And then it will be wise, not by its own light, but by participation of that supreme Light. (De Trinitate)

Memory is the great storehouse of experience and knowledge. It exists on both the individual level and the societal level. We all remember facts, figures, events, commands, consequences, joys, pleasures, and pains. As a collective society, we remember cultural and historic watersheds, landmarks, turning points, formative documents, battles, and public speeches. The memory of these things become the backdrop of our individual and collective identities. As Paul Elmer More wrote:

We suffer not our individual destiny alone but the fates of humanity also. We are born into an inheritance of great emotions–into the unconquerable hopes and defeated fears of an immeasurable past, the tragedies and the comedies of love, the ardent aspirations of faith, the baffled questionings of evil, the huge laughter at facts, the deep-welling passion of peace. Without that common inheritance how inconceivably poor and shallow would be this life of the world and our life in it!

These are the raw materials of our cultural memory. These raw materials are then shaped and molded and formed into something coherent and intelligible through our cultural understanding of how the world is structured. Our governing worldview equips us to understand what those events, commands, battles, documents, and pains mean to us, to our own history, and how they have shaped us in particular ways. Furthermore, the what of our memory, and the how of our understanding inescapably lead us to love — love for that someone or something that we believe is the source of all the good that we remember and understand, that to which all our knowledge points. For the Christian, the integration point, the source of all things, the one by whom, and for whom, and through whom all things were made, the living incarnation of truth itself, is Jesus Christ.

The true aim of education, then, can be only defined as the worship, or the magnification, of Jesus. Following Augustine, another way to say the same thing is to define education as the pursuit of wisdom, true wisdom defined as the fear of the Lord. This necessarily involves all three aspects of Augustine’s insight. Education takes the building blocks of memory, shaped by understanding, and leads the pupil to love that which he or she understands to be the foundational principle of it all. That is what education accomplishes, necessarily and inescapably. Man, in his self-centeredness, can substitute himself for Christ and call it education (as did Plato and Rousseau). But only when we remember our Creator, only when we understand all that we see and know by means of His “supreme Light”, only when memory and understanding lead to a deeper love for Christ, only then will we be truly wise. Only then will education have attained its true end.

Wisdom as Telos

To put it simply, wisdom (the fear of the Lord, rightly-ordered worship) is the telos of mankind. This is what we were created for. This, according to Augustine, is why we were given the ability to remember, understand, and love. Education, which is the pursuit of wisdom, therefore has as its telos the same thing: the worship of God. Consider these words of the psalmist from the opening verses of Psalm 78, a psalm given the Israelites to teach them what education was for:

Give ear, O my people, to my teaching;

incline your ears to the words of my mouth!

I will open my mouth in a parable;

I will utter dark sayings from of old,

things that we have heard and known,

that our fathers have told us.

We will not hide them from their children,

but tell to the coming generation

the glorious deeds of the Lord, and his might,

and the wonders that he has done.

He established a testimony in Jacob

and appointed a law in Israel,

which he commanded our fathers

to teach to their children,

that the next generation might know them,

the children yet unborn,

and arise and tell them to their children,

so that they should set their hope in God

and not forget the works of God,

but keep his commandments;

and that they should not be like their fathers,

a stubborn and rebellious generation,

a generation whose heart was not steadfast,

whose spirit was not faithful to God. (Psalm 78:1-8)

Here we see the central goal of education. Imprinting, imparting, and transferring personal, familial, and cultural memory from one generation to the next is the responsibility of every parent (vv.1-4). But memory alone is useless, unless it leads to a proper understanding of ourselves and our world (vv.5-6). However, unless that faithful education leads to a growing hope in God, love for God, obedience before God (vv.7-8), then they have accomplished nothing. Their education has failed in light of man’s ultimate telos.

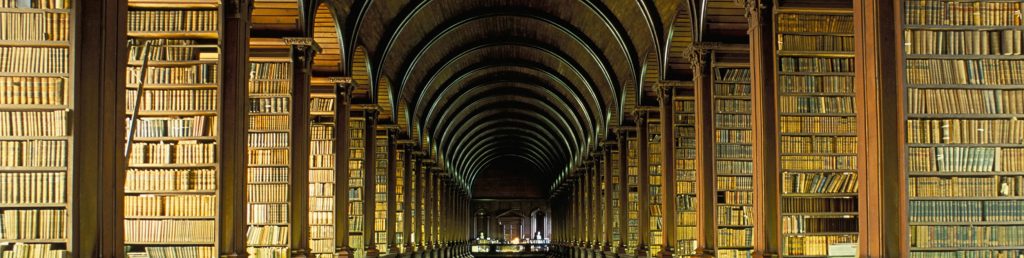

Memory leads to understanding, which leads to love. But if that love is not ultimately directed toward the One who gives the memory, gives the understanding, and is the ultimate source of love itself, then it is infernal. If all the books in the world, great or otherwise, do not support or develop one’s deeper love for and allegiance to Jesus Christ, then all they will do is fill a bookshelf in Hell, rendering all memory and understanding utterly vain, utterly empty of any real meaning. The purpose of rightly ordered education is to draw the soul back to its Creator, to remember, understand, and love Him, who made all things, and thus to grow wise in and through worship.

For the Love of… Something

All education necessarily results in the love of something. Each and every practical instance of instruction will necessarily shape the affections of the pupil’s heart. Love is the inevitable result of human training. At the end of our educational experiences, in childhood or elsewhere, we will end by loving something more — be it ourselves, our society, our subject, our idols, or whatever. Augustine’s point is that whatever we remember and however we understand, if our pursuit of wisdom does not lead us to love God more than every other object of love, then that pursuit is both fruitless and ultimately destructive.

Education is not merely the transfer of data from one cognitive receptacle to another. It is the formation of a human being. Stratford Caldecott, in his book Beauty in the Word, says this: “[E]ducation is not primarily about the acquisition of information. It is not even about the acquisition of ‘skills’ in the conventional sense, to equip us for particular roles in society. It is about how we become more human (and therefore more free, in the truest sense of that word).”

Humans, children or otherwise, can only become more human in the context of other humans leading the way. And, as Psalm 78 makes clear, it is the responsibility of the parents, in the context of a faithful community, to bring up their children to know God, to know the things He has done, so that they put their trust in Him. And to do so in such a way that those children would know down in their bones it was their responsibility to pass on that cultural memory and understanding to the next generation, training them to do likewise with their children, and so on down through the centuries. In other words, education is not just a classroom affair. It is happening in every aspect of life, and especially those communal moments, beginning with the family, passing down traditions and stories, forming and shaping the affections, directing our loves, through the environments we create and inhabit. As Paul puts it in Ephesians 4:11-16, in what could be called a Pauline manifesto on education:

And [God] gave… teachers, to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until we all attain to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to mature manhood, to the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ, so that we may no longer be children, tossed to and fro by the waves and carried about by every wind of doctrine, by human cunning, by craftiness in deceitful schemes. Rather, speaking the truth in love, we are to grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and held together by every joint with which it is equipped, when each part is working properly, makes the body grow so that it builds itself up in love.

Back to Dante

Throughout the Commedia, Dante is schooled by his guides in a right understanding of sin, rebellion, selfishness, salvation, repentance, courage, wisdom, mercy, faith, hope, and above all, the love Paul here refers to. Each infernal canyon, each purgatorial terrace, and each celestial sphere lead the pilgrim to a deeper knowledge, a deeper understanding, and a deeper love for God. This is the true aim of the pilgrim’s education; it must be the aim of our education as well. It is Grace-based and Grace-perfected education, in pursuit of definitive and substantive wisdom, which can only be found in the worship of the Triune God. As Dante discovers, as Augustine had discovered before him, our hearts are restless until they find their rest in Him — our wills are a broken and unbalanced wheel, until they turn with the perfect and holy will of God.

For those unfamiliar with what Roman Roads has to offer, we have an array of excellent texts and curricula, including

Old Western Culture: a fully integrated, 9-12th grade humanities course, touching on literature, philosophy, history, theology, and more, complete with a 16-volume set of original texts, spanning from Homer and Vergil to Jane Austen and CS Lewis;

Calculus for Everyone: a text that gets to the heart of why Calculus works… and why it is important;

Dante Curriculum: an in-depth, canto-by-canto consideration of one of Christendom’s greatest achievements, Dante’s Divine Comedy, from a solidly Christian perspective;

Fitting Words: a course in the classical art of formal rhetoric, training students to speak powerfully and elegantly;

Picta Dicta: A Latin curriculum in which students learn through all four language pathways (reading, writing, speaking, and hearing), making it both more enjoyable for them to learn and easier to retain.

Furthermore, we have a growing collection of standalone works, such as Cicero’s On Duties, Dr. Gordon Wilson’s Darwin’s Sandcastle, Elizabeth Landis’ The Forgotten Realm: Civics for American Christians, and Christiana Hale’s Deeper Heaven: A Reader’s Guide to CS Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy, plus several more.

Comments