Dante, Protestant

Ok, so of course I’m being provocative. Dante was not a son of the Protestant Reformation. His Comedy was published in 1320, a full 200 years before Luther said, “Here I stand…” at Worms. And yes, his epic poem is full of doctrines that make actual protestants squirm. He prays to Mary; he prays for the dead; he holds to a purgatorial state where, even if man is reconciled to God by the blood of the cross, sinful habits that remain at the end of one’s life still must be purged after death before one ascends to Heaven. So how dare I use the words Dante and Protestant in the same title, right?

There are two reasons. First, however faithful Dante was to any number of Roman doctrines, he still maintained a ‘protesting’ voice. He was in no way blind to the many corruptions of the medieval Church, and frequently criticized those false shepherds (both dead and living) who he felt were leading the Church astray. I mean, he put more popes in Hell than Luther ever did. He knew they could err and could err in big ways. His desire, as even a cursory reading of the Comedy makes clear, was to see the Church reform and return to a reliance on the authority of Scripture, to forsake her greed and avarice, to abandon her worldly and immoral hypocrisy, and to wholly embrace her pastoral calling as shepherds not of silver but of souls.

But the second reason I dare to couple Dante’s name with that of Protestant, and I would hope all branches of Christianity can here say amen, is this: in his poetry and philosophy, he creates a rich, full-orbed, and deeply nourishing picture of the transcendence of God that stands in stark contrast to, and protests against, the soul-sucking, mechanistic, naturalism that defines our modern, secular world, and, to a large degree, the modern, secularized Church. Dante’s Comedy continues to preach and embody an understanding of God, the imago dei, the telos of creation, and the exhaustive lordship of Christ that protests strongly against the gnostic enlightenism that has come to rest not only over all of modern Christendom, but over the evangelical world especially, these last couple centuries. In sanctifying and sending our imaginations into orbit around the centrality of Jesus, Dante offers a prophetic and protestantic voice from the past that speaks directly to our culture, in the here and now.

Born in 1265, Dante is part of Christendom’s shared heritage. He stands downstream from the likes of Augustine, Ambrose, Anselm, the Cappadician fathers, Chrysostom and many others that we would praise for being brothers in the Lord and faithful preachers of the Word as evangelical protestants. I might take issue with various aspects of their theology, but that does not, nor should it stop me from appreciating their invaluable contributions. So it is with Dante. Do I want to embrace everything that the 13th century poet embraces? Of course not. But I would say the same thing of C.S. Lewis, while still holding on to his many works of brilliance that exalt Christ. It is true, the medieval, pre-reformation doctrines can be distracting for protestants. But given the understanding that existed at that time, I do not believe they actually detract from the exaltation of Christ like we might think, but rather support it. I hope to convince you of this in my Reader’s Guides on Purgatorio and Paradiso.

More could be said, obviously, and will in forthcoming publications, but if I could say one thing, especially to those modern evangelical protestants, like myself, who are unsure about diving into the Comedy, it would be this: in my opinion, no other poem immerses the reader so completely into a Christ-centered, Christ-exalting understanding of the cosmos as does the Comedy. Now, for the Milton lovers who just jumped to their feet, ready to do battle, let me explain what I mean, as the central difference I see between Dante and Milton will actually illustrate my point. Paradise Lost asks the reader to stand and watch from the sidelines as justifications unfold. Don’t get me wrong, it is a brilliant poem, and thoroughly Christian, even Calvinistic. But it still is a product of the early modern era. It presents arguments for inspection. By contrast, Dante forces you into the experience of the poem. Readers of the Comedy immediately become pilgrims themselves, and walk through the various realms with Dante. Milton beautifully, majestically explains the mechanism of a grand and glorious roller coaster, if you will, and in a way that is profoundly helpful and nourishing. Dante, on the other hand, demands you get in, sit down, and shut up.

It is in this way I would argue that the Comedy is superior to every other poem in the history of Christendom. The poem does not try to justify God; it assumes His authority from the opening lines, and forces the reader to deal with it. Furthermore, from the opening lines, it is a poem that identifies us as the problem: not Satan, not fallen angels, not worldly inticements, or anything else external to us. Anticipating Dostoevsky, Dante preaches that I am what is wrong with this world; I am the one asleep and straying from the true path into any number of corruptions; I am the one in need of radical Spirit-guided sanctification; I am the one who needs my will to be moved by the Love that moves the sun and the other stars. Because right now, at the beginning of the Comedy, that’s not me. In doing daily battle with my flesh, I need as many reminders as there are minutes remaining in my life, that Christ alone is King and that all things exist because of Him and for His glory. I need to be reminded that each and every moment given to me is one in which I am either facing the King as a loyal subject, or turning from Him as a would-be usurper of His authority. Dante, like no other, helps me not only understand these truths in rich and profound ways, but personally experience them as well.

In the end, the differences of doctrine that exist between this 13th century poet, and me, a 21st century evangelical protestant – which do exist, and are not insignificant – are still far outweighed by the benefit of being confronted with my own infernal habits, and utterly gobsmacked by my own impoverished imagination. Reading Dante alerts me to just how small my understanding of God and His creation is, and how large I loom by comparison. I must decrease, He must increase; and I need to get my hands on whatever tools can be used to help toward that end. This is what the Comedy can do, and it is priceless.

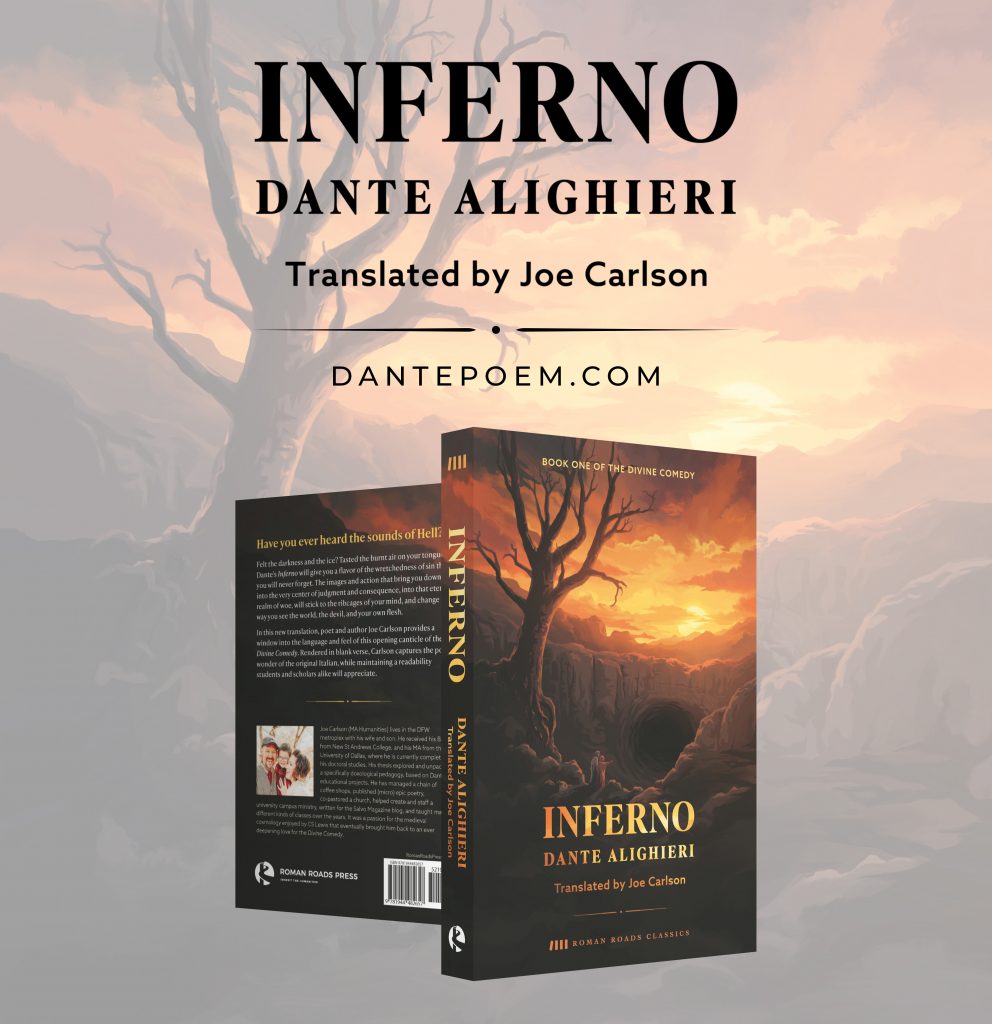

Joe Carlson (MA Humanities) lives in the DFW metroplex with his wife and son. He received his BA from New St Andrews College, and his MA from the University of Dallas, where he is currently completing his doctoral studies. His thesis explored and unpacked a specifically doxological pedagogy, based on Dante’s educational projects. He has managed a chain of coffee shops, published (micro) epic poetry, co-pastored a church, helped create and staff a university campus ministry, written for the Salvo Magazine blog, and taught many different kinds of classes over the years. It was a passion for the medieval cosmology enjoyed by CS Lewis that eventually brought him back to an ever deepening love for the Divine Comedy.