Hell is Obscene

For those coming to Dante’s Inferno for the first time, you might be surprised to find brief instances of vulgarity coming out of the mouth of the narrator. “This is a Christian poem…why are there bad words?!” And the question really is directed at me, as the translator. “Couldn’t you have used ‘crap’ or ‘poop’?” Well, I could have. But I didn’t, and I wanted you to know why. The primary reason is that Dante didn’t pull any punches, and so I didn’t want to either. But more than that, one of the great benefits of reading the Inferno, and something I will discuss at length in a future article, is that the pilgrim’s journey through Hell primarily gives us two things:

1) a tangible feel for the consequence of sin, and

2) an utter repulsion for the character of sin.

Not that this, in and of itself, stops anyone from sinning. Only the Holy Spirit can do that. But it is a helpful reminder of what sin actually is. Sin is disgusting. Sin is filthy. It rightly belongs at the extreme end of the universe, as far away from God as possible. If our Redeemer casts our sins away from us, as far as the east is from the west, Hell is one of those poles. And imaginatively walking through Hell is a potent reminder of what that sin is, and what it does to human nature.

In short, Hell is obscene. And the language necessarily reflects that. Three times Dante the poet uses the Italian word merda, which is the equivalent of the English “shit”. Two of those times are in Canto XVIII. Passing over the second ditch of the eighth circle of Hell, the travelers meet the flatterers, who are submerged “in an excrement / that seemed to have come from human privates” (Inferno XVIII, 113-114). Dante then looks more closely and sees the soul of one Alessio Interminei. However it takes the pilgrim a while to recognize him because his head was “so filthy with shit, / whether he was lay or clerk was not clear” (Inferno XVIII, 116-117). Benvenuto da Imola, a 14th century commentator on the Divine Comedy, said this about poor Alessio, “[he] had a terrible habit: he was so given to fattery, that he was unable to say anything at all without seasoning it with the oil of adulation. He greased everyone, he licked everyone, even the most vile and venal servants. In short, he completely dripped with flattery and stank of it.” If Dante was writing today, he would have called Alessio a kiss-ass.

A couple lines down, Virgil points out Thais (of Meditation, from Thais fame), a notorious flatterer and whore. Well, as beautiful as the song by Massenet may be, in the second ditch of Malebolge, she is described as a “filthy and frowzy wench / that claws herself there with her shit-filled nails, / now squatting down, now standing on her feet” (Inferno XVIII, 13-132). This is what her flattery has brought her to: squatting in human filth, scraping human filth off of her skin, getting that human filth lodged in her fingernails. It’s not a pretty picture.

But that is exactly the point. Flattery is disgusting. It is a wicked use of the intellect, of God’s gift of rationality. Everyone in Malebolge (including these flatterers) is punished for fraud, the use of trickery and deceit to bring advantage to self at the expense of others. In Dante’s framework, fraud is more hateful to God because it employs that particular human faculty that identifies us as His image bearers. If we use the very gift that distinguishes us from the beasts, in order to act like beasts toward one another, what does that say about us? If we use the faculty of speech and praise in a cold and calculated way to lie and deceive for the sake of personal gain, what is it coming out of our mouths? What comes out, in modern parlance, is just a bunch of BS. Well, in Dante’s Hell, how you live follows you into death and defines the state of your eternal suffering. The BS coming out of the mouths of the flatterers while they lived may have sounded like praise. But here in the second ditch of Malebolge, it is shown for what it truly is. Alessio and Thais have found that out the hard way.

There are places and things that warrant such strong and obscene language. Hell is one of those places, and flattery is one of those things. Being faithful to Dante’s word choices allows us to receive the full impact of his imaginative landscape. And this is why it is helpful. The disgusting imagery and the language of the poem creates associations in our minds, and for our affections, between certain actions and certain consequences. That pungency attaches a strong negative feeling to the actions depicted. In other words, if we meditate on the second half of Canto XVIII for any length of time, we will come away realizing that flattery really is as disgusting as Dante depicts. And maybe, just maybe, the memory of that smell will linger in our minds the next time we are tempted to spout a bunch of BS while kissing up. And maybe we will finally realize how disgusting our sin actually is.

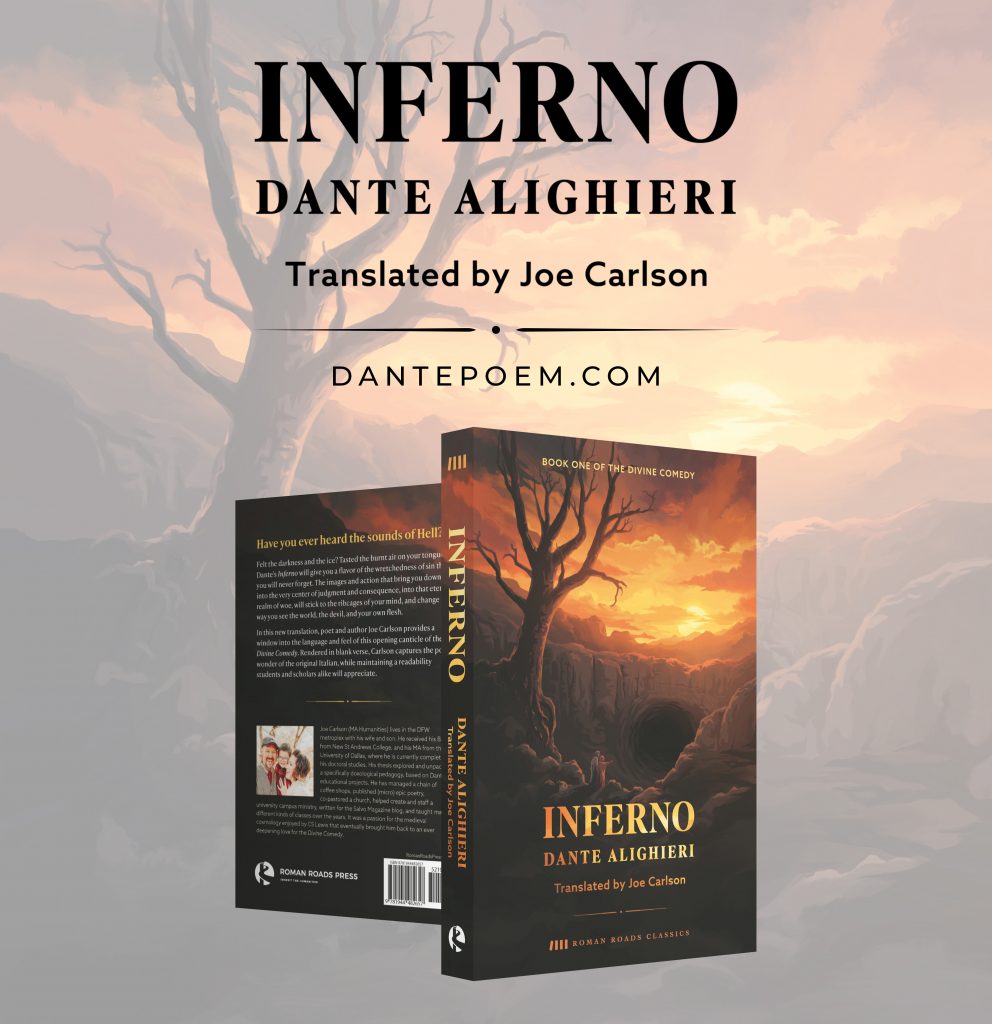

Joe Carlson (MA Humanities) lives in the DFW metroplex with his wife and son. He received his BA from New St Andrews College, and his MA from the University of Dallas, where he is currently completing his doctoral studies. His thesis explored and unpacked a specifically doxological pedagogy, based on Dante’s educational projects. He has managed a chain of coffee shops, published (micro) epic poetry, co-pastored a church, helped create and staff a university campus ministry, written for the Salvo Magazine blog, and taught many different kinds of classes over the years. It was a passion for the medieval cosmology enjoyed by CS Lewis that eventually brought him back to an ever deepening love for the Divine Comedy.