An Intro to Dante, by Dante

This Article is an excerpt from the introduction to Inferno: Reader’s Guide.

Dante Alighieri finished his Comedy (it was only called the Divine Comedy after his death) in 1320. He dedicated the final volume, Paradiso, to his friend and benefactor, the “magnificent and most victorious Lord, the Lord Can Grande della Scala.” In a famous letter written to his patron, Dante acknowledges the helpfulness of introductions. He says,

If any one, therefore, is desirous of offering any sort of introduction to part of a work, it behooves him to furnish some notion of the whole of which it is a part. Wherefore I, too, being desirous of offering something by way of introduction to the above-mentioned part of the whole Comedy, thought it incumbent on me in the first place to say something concerning the work as a whole, in order that access to the part might be the easier and the more perfect.

Dante Alighieri, The Letters of Dante, trans. by Paget Toynbee. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1966), 198.

He goes on to describe his great poem as “polysemous,” a work with multiple meanings, or multiple layers of interpretation. These include the literal, the allegorical, the moral, and the anagogical, or eschatological. Students of medieval theology will recognize here the quadriga, the fourfold method of interpretation. In his letter, however, he only touches on the literal and the allegorical, inferring that the moral and anagogical follow from and are wrapped up in the allegorical. He says:

The subject, then, of the whole work, taken in the literal sense only, is the state of souls after death, pure and simple. For on and about that the argument of the whole work turns. If, however, the work be regarded from the allegorical point of view, the subject is man according as by his merits or demerits in the exercise of his free will he is deserving of reward or punishment by justice.

Dante, Letters, 200.

The structure of the poem depends on the first meaning; it is the literal sense of the afterlife that gives movement and direction to the whole work. Without the context of the three stages, the “argument of the whole” has no foundation. But the “argument of the whole” also needs to be understood allegorically if the whole is to be in any way beneficial to the reader. Put more simply, while Dante uses the afterlife to stage his drama, the deeper purpose is to demonstrate the soul’s journey, either to or away from God. Essentially, the Comedy is a travel guide, walking us through a deeper understanding and hatred of sin (Inferno), a practical guide to sanctification (Purgatorio), and the true nature and source of holiness and gratitude (Paradiso). Throughout, Dante offers us an imaginative landscape of human affections, both in their corrupted, self-oriented state, and as they are when rightly ordered toward God.

If you are, like me, an evangelical protestant, the words “merits… free will… rewards” from the above quote will likely freak you out. Don’t worry. These guides will work through all the various issues that present themselves. There certainly are theological elements of the Comedy that, as a son of the Reformation, I would express differently, or flat out disagree with — I would want to shy away from prayers for the dead, for instance. But I would suggest that there are not as many problematic passages as you might suppose. Part of the tension comes from a difference between moderns and medievals in how we talk about various Biblical truths; and part comes from what I believe is a mistaking the literal meaning for the allegorical. I am convinced that Dante was more interested, for instance, in prayers offered for those being sanctified here and now in this life (the allegorical interpretation) than for those who have already died (the literal interpretation). He likely did hold to that doctrine as a Christian of the 13th and 14th centuries, but the specific teaching concerning praying already dead souls into Heaven is not necessary to the deeper meaning of the poem. Purgatorio was written for our benefit, for those of us who are still alive and reading the poem. Thus its lessons are meant to be translated and applied to our own journey toward God. The rehabituation that defines that canticle, therefore, is the rehabituation of sanctification, the sanctification of souls already purchased and redeemed by the blood of Christ. This, and other topics like it, will be discussed in more detail in the cantos where they come up, but hopefully you get my point. There is a deeper significance to the poem, a deeper significance Dante himself alerts us to, than the doctrines specific and local to his particular time and place — doctrines which we may or may not agree with when considered in isolation.

In short, there is much that non-medieval, evangelical protestants have to learn from this great work, if only we will submit ourselves to the poem, and show the courtesy and charity our brother in the Lord deserves. At the heart of the poem is a rich and profound understanding of who man is and what man is for. It is a poem that answers the fundamental questions of ultimate meaning and purpose, of existence itself. And it does so in a way that will rekindle a dormant, if not entirely extinguished, flame of transcendent wonder. It offers us the opportunity to experience a re-enchantment of the world, in which the whole created world is again understood to be a window into the goodness and faithfulness of the Creator, through which the Spirit is drawing us closer to Christ.

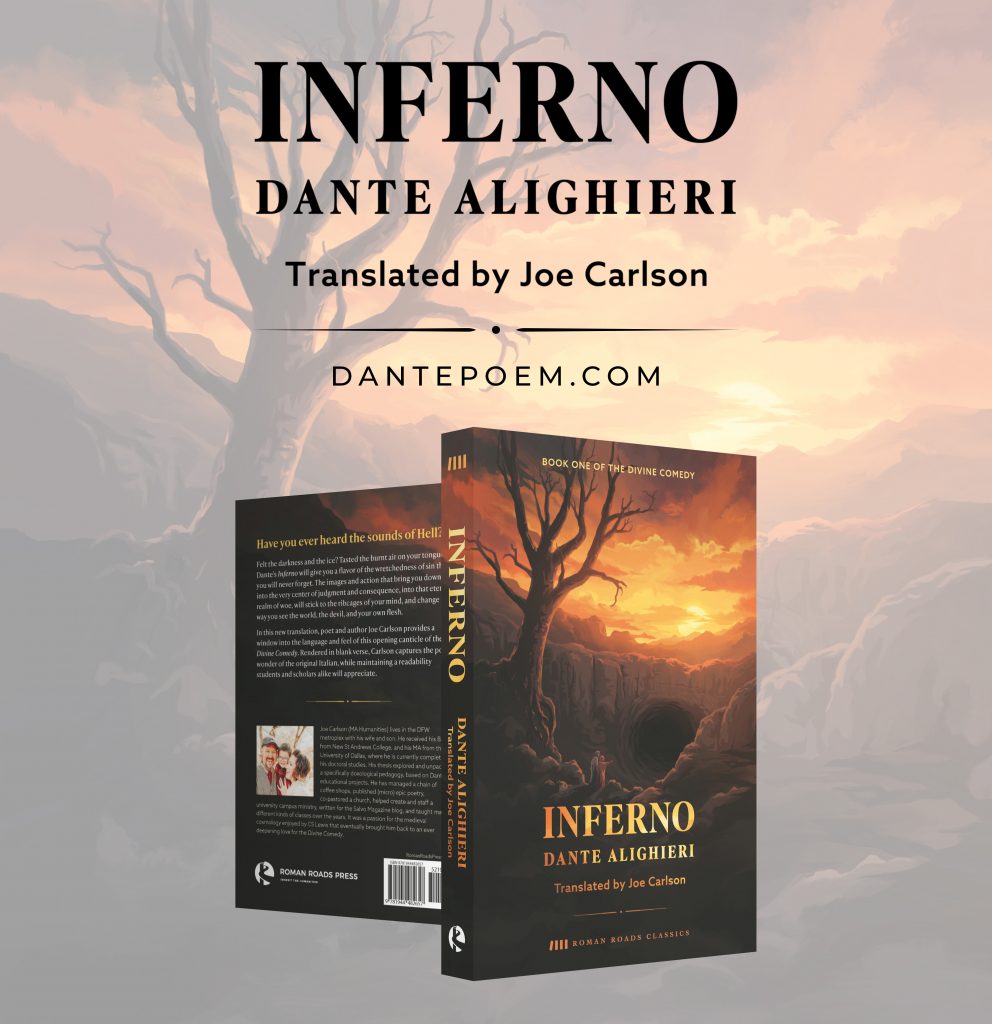

Joe Carlson (MA Humanities) lives in the DFW metroplex with his wife and son. He received his BA from New St Andrews College, and his MA from the University of Dallas, where he is currently completing his doctoral studies. His thesis explored and unpacked a specifically doxological pedagogy, based on Dante’s educational projects. He has managed a chain of coffee shops, published (micro) epic poetry, co-pastored a church, helped create and staff a university campus ministry, written for the Salvo Magazine blog, and taught many different kinds of classes over the years. It was a passion for the medieval cosmology enjoyed by CS Lewis that eventually brought him back to an ever deepening love for the Divine Comedy.

Comments